Rigel Walshe

Software developer, Swan Bitcoin

A Quasi-transcript of my Talk at Baltic Honey Badger 2022.

When I write a talk I generally try to sketch out the content in writing first. This is the cleaned-up content of that sketch for the talk I gave at Baltic Honey Badger 2022, rather than a direct transcript.

I should probably preface this by clearing up that the Psychopaths and Sociopaths here are not intended to refer to their actual psychological definitions, which are quite similar to each other. Rather the meme of the Bitcoin enthusiast rabidly and aggressively responding to any perceived threat to Bitcoin, and the slimy self-interested narcissist from David Chapmans article I refer to below.

What inspired me to write about this topic is my background. Since I was 17 I’ve played in a couple of crazy metal bands, recorded several albums and toured around the world. That gave me a lot of insights into how subcultures work, how they change, how they do or do not become mainstream, and how some of the internal politics has an outsized influence on the collective direction of a movement where no one is really in charge.

Also, I was a police officer for ten years, which showed me a different type of cliquey subculture. And that when stakes are as high as they can be, why rules and gatekeepers function as a way to enforce group norms that you don’t have the luxury of time to explain to newcomers or outsiders, and how this can metamorphosis into what people would generally describe as a toxic culture.

I first brought Bitcoin in 2014, but it wasn’t until I started to come to conferences around the world in 2018 regularly that I noticed how strong the similarities between what I have seen in both of these worlds, music and the police, and in the Bitcoin meatspace. Same mistakes, same benefits. As Bitcoin has become more and more mainstream, those correlations have only become stronger and more pronounced. But there isn’t a lot of nuanced discussion in the Bitcoin space about how human behavior and culture will play a significant role in the success or failure of Bitcoin and how we can approach this in an informed and detached fashion to use this in our favor.

We talk a lot about hyperbitcoinization and throw around some simple concepts like the Rogers adoption curve on Twitter but discuss little about what that mass adoption means. How an influx of masses could alter what Bitcoin actually is. I wrote an article called the Bitcoin Rorschach test. I made the point that Bitcoin is just a GitHub repo, its code. It’s the users and their behavior that define what Bitcoin really is.

I think Eric Voskuil said it best —

“Bitcoin is not secured by blockchains, hash power, validation, decentralization, cryptography, open source or game theory — it is secured by people.

Technology is never the root of system security. Technology is a tool to help people secure what they value. Security requires people to act. A server cannot be secured by a firewall if there is no lock on the door to the server room, and a lock cannot secure the server room without a guard to monitor the door, and a guard cannot secure the door without risk of personal harm.

Bitcoin is no different, it is secured by people who place themselves at personal risk. Sharing this risk with other people is the purpose of decentralization. A centralized system requires one person to shoulder all of its risk. A decentralized system divides risk among individuals who comprise system security. Those who do not understand the value of decentralization most likely do not understand the necessary role of people in security.”

The technology of Bitcoin gives us the potential for censorship-resistant, permissionless, sound money. But if people are not motivated to run nodes, to send and receive Bitcoin as payment in a sovereign manner, if they just keep their coins on exchanges, trust wallet APIs to send their transactions or verify their balances, or are too afraid of government enforcement, exchange bans or taxes to use it as freedom money then this remains only potential.

Its all good and well having great technology or innovations in privacy and sovereignty, but if a significant enough percentage of Bitcoin users don’t bother to learn how to use them correctly and with discipline but instead choose convenient third-party solutions, then Bitcoins potential risks being captured by corporate or government interests, and indeed I believe this the easiest and most likely way for Bitcoin to fail.

So culture matters, but no one really talks about how as things get bigger and more and more new entrants become Bitcoin users, what this means for it’s culture and, therefore, their influence on Bitcoin itself.

If culture matters, it would help to clarify what sort of cultural phenomenon Bitcoin is. Bitcoin as it is isn’t mainstream, maybe everyone knows what Bitcoin is, but we’ve got a long way in terms of user numbers and day-to-day usage before we get to something that’s really mass adopted. Something thats as ubiquitous and boring as using a cellular phone. So Bitcoin is still a subculture, or more specifically, I’d argue a counterculture. If we want to understand how things are likely to play out, we want to understand what a subculture and counterculture are and what has happened as others have gone mainstream.

The easiest way to define what subculture is, is ‘me and the boys’, a group of people who do things a little differently. They have their own set of values, and their own way of doing things. When you start hanging out with a group of friends regularly, you begin to adopt a similar way of speaking. You have a shared set of references, jokes that outsiders don’t quite get. A subculture is really just a larger-scale version of that.

Subcultures, as we know them in society, are things like these. It’s possible to be a member of more than one. It doesn’t exclude you from mainstream society. It’s seen as a quirky thing that you do, maybe seen as something a little weird but not that’s ‘wrong’ or ‘bad’. It still fits within mainstream society.

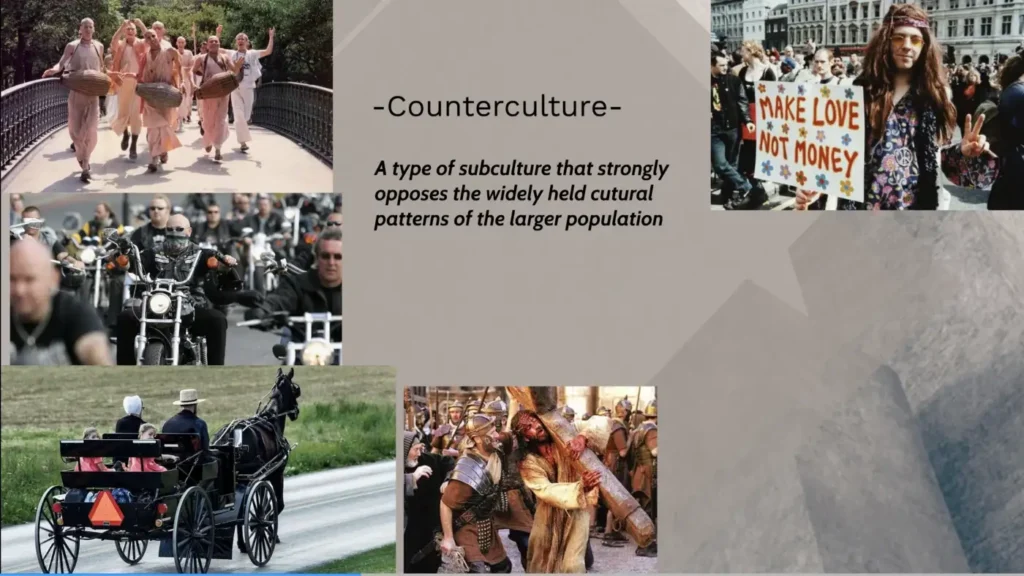

But there’s a subset of subcultures called countercultures. Countercultures are a type of subculture that not only does not fit in but actively opposes widely held cultural patterns in the larger population. There is a sense of pride and attachment to the idea you are not the same as mainstream society, that you are living by a different value system.

This can be as extreme as something like the Amish or outlaw motorcycle gangs or religious cults where you are clearly differentiated from mainstream society, or it can be something more like the hippy movement where you coexist inside society as a group that still prides itself on shared values that oppose the status quo.

Counter cultures exist to change mainstream culture. They often base themselves around drawing attention to some of the contradictions, hypocrisy, or problems the dominant culture doesn’t want to address: the elephant in the room. So unsurprisingly, often innovation and change in society is driven by countercultures. For example, most of the first property-owning women in the United States were the madams of brothels. At the time, a woman owning property was seen as weird, unnecessary, and maybe even counter to the rules of a functioning society. But as a madam, you were already an outcast and a reprobate, social pressure didn’t mean anything, and that gave them the freedom to imagine different ways of doing things. In this instance eventually, society realized there was obvious value here, and it became normalized.

Some say there’s no such thing as Bitcoin culture, and I think there’s a nugget of truth to that, but equally, as I started out saying, culture is just the collective sum of user behavior, the way things are done in aggregate. So if you could possibly lump all the different opinions and world views of ‘Bitcoin users’ or ‘Bitcoin owners’ into some overarching term like ‘Bitcoin Culture’ I think you’d have to agree that whatever else it is, its best defined as a countercultural movement, something that prides its self on its difference from and opposition to the status quo. If we understand that we can start to draw on history to understand the good and the bad as other countercultures have become more mainstream and eventually influenced and have been absorbed into society.

Some examples we could look at are the gay community, punk rock, hip hop, and cannabis culture. All these things started as radical countercultural movements and ideas, but now they are pretty bland and have lost much of what originally made them gritty and magnetically interesting. Partly you could say this is because they have genuinely transformed society, what made them different has been normalized, and partly because they have been commodified and turned into objects by people who saw an opportunity to exploit their energy for commercial or political gain. Just as a countercultural idea attempts to exert itself on society by changing the status quo, the status quo attempts to exert itself on the counterculture.

We call this ‘commodification’, and to effectively commodify something, you need to make it suitable for the status quo, for the mass market, something that’s easy and convenient to understand and desirable for a large number of people. Usually, this means presenting a highly curated and idealized picture of what the idea actually is, playing up the parts that are highly monetizable or marketable, and discarding or playing down the elements that are not. This takes place via two processes- diffusion and defusion.

What is diffusion?

For an idea to be desired by the masses, they first have to know that it exists and why they want to participate in it. It needs to be distilled into something that can be shouted from the rooftops, that is presentable in a 10 second advertisement on Tiktok or Instagram. It needs to be able to be distilled into a simple memorable slogan or mantra, into soundbyteable messages and images easily communicable to and understood by even the lowest common denominator. Usually, it means the nuance, subtleties, and context behind the idea are diminished and what is presented to and understood by newcomers is a much more simple picture than reality.

What is defusion?

Countercultures base themselves on active opposition to the status quo, the very masses that commodification is targeting. Therefore, to bring those same masses on board, there needs to be a depoliticizing or ‘watering down’ of an idea’s values, meanings, ideals, and subversive potential, Altering the meanings of things that may not have been palatable or acceptable to some percentage of the general public. Usually, this means prioritizing convenience, focusing on the enjoyable, positive aspects, and downplaying or ignoring those that are not, sometimes even misinforming the audience about what the thing actually is. This creates friction among participants and distorts what the idea is about as more new entrants enter.

Via diffusion the market diminishes the richness and nuance of the idea, via defusion it neuters it and diminishes its potential for radical change. Both to make it easier to be packaged, distributed, and consumed by your average Joe and to massively increase the number of people who are part of (or believe they are a part of) a counterculture. Usually, the goal is to capitalize on this mass influx of people financially; sometimes it’s to capitalize on them politically, but always it’s with the intention of prioritizing numbers over nuance. Sometimes it’s a well-intentioned belief that if you want to bring about change, there is strength in numbers, and sometimes it’s purely opportunistic greed by people who see societal change as a means to increase their financial or political standing.

So what happens exactly when you take a countercultural idea and try to funnel a ton of new people into it? We can look at a couple of different frameworks based on the mainstreamification of other subcultures and countercultures to unpack what’s likely to play out as Bitcoin grows and becomes more of a part of the mainstream.

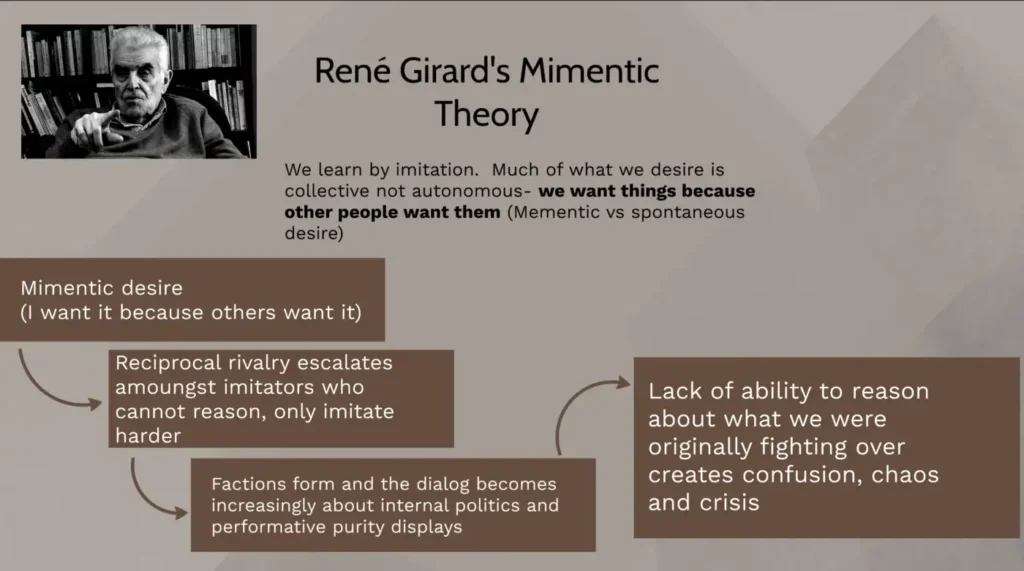

The first is Rene Girard’s Mimetic theory.

As human beings we often learn by imitation. As children, we learn to imitate our parents doing things that we are not yet able to comprehend, and as adults, our time and focus are limited. Very little of what we learn and, by extension do is by conscious examination rather than parroting those we aspire to be more like. Desire is a social process, and our desires are often caught by contagion. It is not autonomous but collective.

We want things because other people want them.

There is a distinction between spontaneous desire, the desire for the thing itself, and mimetic desire, wanting something because you want to emulate or imitate someone else. Early adopters of Bitcoin came because they were interested in the technology or the potential for social change, but as any phenomenon becomes bigger and bigger, more people become involved simply because of the volume of noise. ‘It’s the thing all the cool kids are doing’. They want it because everyone else wants it, not because they arrived at it through their own exploration, reasoning, and understanding. As things become diffused, as we discussed before, this becomes more common. If you see billboards for Bitcoin or Crypto every mile or so like I did this year coming from the airport to the hotel in Miami for the Bitcoin 2022 Conference, you start to attract people who are interested in Bitcoin not because they have rationally arrived at desiring it, but out of the natural human proclivity to go along with what other people are talking about.

People become interested in Bitcoin not because they find Bitcoin itself interesting but because they believe Elon Musk is a smart, successful guy. If he is talking about Bitcoin then I should be too. His tweets can pump or dump prices because a sizeable cohort of the world will buy Bitcoin not because they actually want or understand the asset itself but because they want to be like Elon Musk. Additionally, because these new entrants learn via imitation, they cannot objectively and critically reason about the thing, only mimic the words and talking points like a child to a parent.

Memetic theory states that as things gain social traction and become more desired, the participants engage in escalating one-upmanship towards the thing they desire. As they cannot objectively form opinions about it, they base their actions on looking at the words and actions of others, then trying to go one step further. As this happens, focus splinters and factions start to form around groups of participants. In turn, this further increases the mimetic appeal of the hustle and bustle of ever larger numbers of people fighting over the thing. Eventually, the focus shifts from the object to the conflict itself. All the talk becomes about the internal drama and politics of the participants rather than the thing itself. New participants understand the space only as an arena competing for human attention rather than the pursuit of truth, knowledge, or material items.

This lack of differentiation or ability to reason and objectively quantify a position about an object of desire descends into tribalism, and the discussion devolves into performative displays of purity and allegiance towards the various factions.

Next is the framework of Geeks, Mops, and Sociopaths by David Chapman.

David’s model explains that as fringe subcultures catch on there’s an invasion of newcomers who often end up spoiling them.

A phenomenon starts with creators who invent an interesting thing- a religion, music genre, political theory, software, etc. Together they create a scene. They share energy and riff off each other, creating something new and innovative.

This attracts Fanatics, people who are not creators but are attracted to what is being created. They become the mortar in the bricks, contributing time, money, organization, and logistics. Both are geeks, they spend all their time and energy understanding the thing, talking about it, and learning about its ins and outs. Some things remain a niche geeky hobby, but if it’s exciting enough and importantly can be appreciated without being too detailed or geeky, it attracts another group, the Mops.

Mops are fans who show up to have a good time but contribute as little as possible. They are not all bad, they bring the mass to take a subculture mainstream. They reinforce the validity of the creator’s ideas, they bring numbers and usually money that at scale, can make the thing an economic force and allow the creators and fanatics to go pro. But unlike the geeks, their motivations lack altruism for the thing. They just soak up the good stuff and complain about what someone else should be doing to solve their problems with it. They dilute the culture with demands for less weird and complicated versions of the thing that are easier to digest. Rather than spending all their time and energy talking about the thing, they want to talk about politics, sports, or fad diets. They treat the fanatics like wait staff. At this point, all of this can start to make the fanatics jaded, who may begin disappearing or losing interest in the thing..

Often at this point our final group, the Sociopaths show up. Creators have created cultural capital, Fanatics have created social capital, Mops have provided liquid capital, and Sociopaths see an unexploited opportunity to manipulate and extract all three. To the Mops, Sociopaths look and sound just like creators, but they dress better and talk smoother. The Sociopaths become the coolest kids in the room and start to extract the money, connections, and sex that the Geeks were never very good at extracting from the Mops. They use their position of authority with the Mops to strip mine the thing. Eventually, they use up all the ‘cool’. The thing becomes so diverted from its original form in the name of commercialization that it no longer has appeal, the mops start to dissipate, and the Sociopaths re-brand themselves as thought leaders of the next exploitable thing.

The last is the Eternal September.

It’s a shorthand for when the firehose of new users becomes too great for the gatekeepers of existing culture to manage. In the early 90s, one of the first communication mediums to take off on the internet was Usenet, which was the first version of what we would probably call forums today. At the time, Usenet generally required a University email, and it was only used by a small number of Geeks who developed some unspoken rules and etiquette that made it an enjoyable, functional place to be, some of which were counterintuitive to a new user. In the early 90s, Usenet was a fantastic place where people experienced for the first time the ability to communicate with strangers all over the world instantaneously about any number of weird topics or interests. However, every September a new influx of college freshmen would be given Usenet access, and they would show up, not knowing the culture, and fuck things up for a little while until they were ‘educated’ by the existing users.

However, in 1993 AOL began providing Usenet access to its subscribers. This meant that the constant stream of new users became too large a cohort for the existing culture to absorb them. From 1993 it was always September on Usenet, the annoying new guy who didn’t get it was the norm, not the exception. Bitcoin has its ebbs and cycles of new users primarily related to price, but we’re at the point of having entered Bitcoins Eternal September. Those who’ve been around for many years understand things about Bitcoin that are hard to communicate in a medium article or a tweet. They need to be experienced and understood over time, in a sense, like many things you have to teach children. But the Eternal September is an unrelenting wave of this every day. Imagine if you owned a restaurant and you had to teach customer after customer how to use a knife and fork every day. This is what we face with Bitcoin’s Eternal September, wave after wave of new Bitcoiner who doesn’t know the first thing about the etiquette or functionality of Bitcoin, why decentralization matters, why trusted third parties are security holes, why ripple won’t go to 589 USD. It doesn’t matter if you like it or not, they are coming. The only answer is to accept that it’s always September in Bitcoinistan.

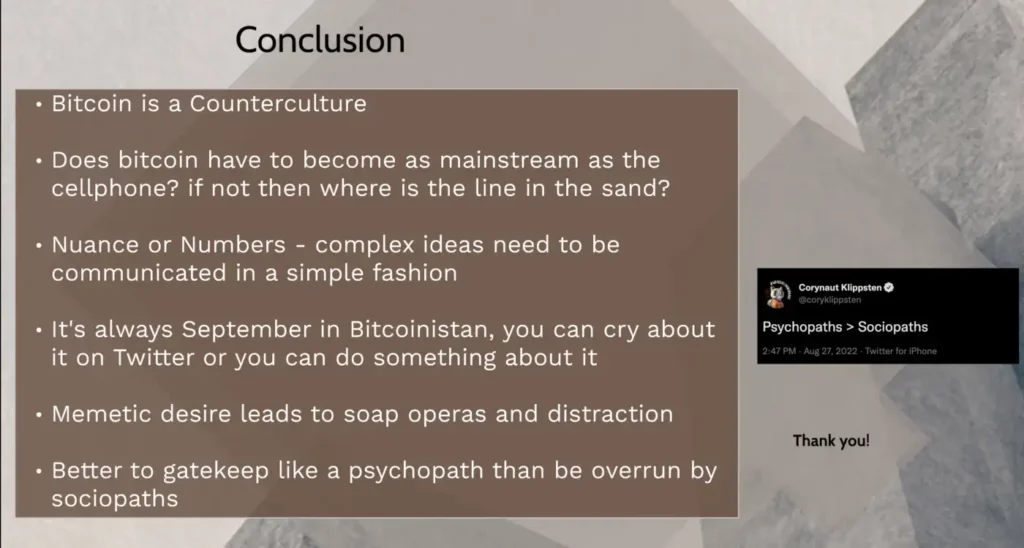

To close out we can summarise the above into a few points.

-Bitcoin is a Counterculture.

As it grows, there will be an existential tension and a zero-sum trade-off between how much Bitcoin changes the status quo and how much the status quo changes Bitcoin.

-This leads to the question, does Bitcoin need to be as mainstream as the cell phone?

If no what’s the line in the sand, and how can we articulate that in detail?

Is KYC acceptable if it makes it convenient for new waves of soon-to-be radicalized Bitcoiners to come on board? How far should we permit new layer 2 technologies to trade sovereignty for convenience as a vehicle to onboard millions of new users when the prevalence of lightning-enabled commerce in El Salvador might suggest apathy is a greater issue? If we do not have clear answers in either direction to these and many other questions, then others will answer these questions for us.

-There is a trade-off between nuance and numbers.

Complex ideas need to be simplified and communicated in a fashion that the lowest common denominator can grasp, but that does not make things so ambiguous that the core tenants are misunderstood.

-It’s always September in Bitcoinistan.

You can cry about it or do something about it. We should forgive the noobs, for they knoweth not what they do. It is on us to keep the door open, to educate and be welcoming to those who want to learn, and we need to provide them with information and the ability and space to reason about Bitcoin.

-Memetic desire leads to soap operas and distraction-

Because if we don’t provide them this information and the ability and space to reason, it leads to memetic noise from newcomers. New entrants who cannot reason and can only parrot the words of others, a world where it’s easy for sociopaths and personality cults to derail the conversation and lead it towards something that would further their ego and finances.

-Better to gatekeep like a psychopath than be overrun by sociopaths.

If we look at Chapman’s model, subcultures are destroyed by people who don’t understand and have reverence for what makes them special. They’re just there for their own selfish ends.

They ruin good things because they kill the golden goose. They don’t understand that altruism is self-interest. But if no one has articulated what that altruism means, what are the core principles that make a cool thing cool, then how can they?

It is on us to define these principles. And to the new entrants who arrive, to clearly disseminate these principles. And against the Sociopaths, we must defend them and defend them like a Psychopath.